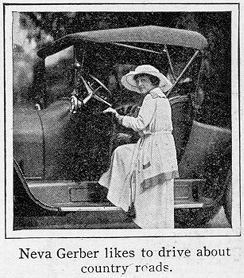

In the era when the Progressive Movement fostered a dynamic feminism, the new emphasis on female independence in business, the professions, politics, and above all, in automobiles, was celebrated in films which were shown in theaters all across the country. It has been said that "no other medium has been more responsible for influencing our attitude towards the automobile or reflecting its role in our culture than the moving picture." (10) The image of a beautiful actress driving a real car on a real highway at a fast speed provided a particular thrill for early movie audiences--and a shining example of woman's new freedom unshackled from the weight of tradition. At the same time, the popular new fan magazines, faithfully recording the personal lives of the stars off-screen for a public hungry to learn everything about them, often highlighted their love of driving. And while male stars on and off screen shared their feminine counterparts' passion for cars, it would seem to be the actresses' skill behind the wheel that made the greatest impression on the public at the time. After all, it was the actresses, not the actors, who were shattering Victorian ideals of gender roles through their yen for driving fast cars. Indeed, driving became a virtual prerequisite for actresses in action-filled films produced when car chases in those pre-back projection days could not be faked in a studio. The majority of the silent film actresses in the teens soon learned to drive and reaching far greater numbers of people than books and stage plays, the moving picture undoubtedly played a decisive role in legitimizing woman's place at the wheel.

In the era when the Progressive Movement fostered a dynamic feminism, the new emphasis on female independence in business, the professions, politics, and above all, in automobiles, was celebrated in films which were shown in theaters all across the country. It has been said that "no other medium has been more responsible for influencing our attitude towards the automobile or reflecting its role in our culture than the moving picture." (10) The image of a beautiful actress driving a real car on a real highway at a fast speed provided a particular thrill for early movie audiences--and a shining example of woman's new freedom unshackled from the weight of tradition. At the same time, the popular new fan magazines, faithfully recording the personal lives of the stars off-screen for a public hungry to learn everything about them, often highlighted their love of driving. And while male stars on and off screen shared their feminine counterparts' passion for cars, it would seem to be the actresses' skill behind the wheel that made the greatest impression on the public at the time. After all, it was the actresses, not the actors, who were shattering Victorian ideals of gender roles through their yen for driving fast cars. Indeed, driving became a virtual prerequisite for actresses in action-filled films produced when car chases in those pre-back projection days could not be faked in a studio. The majority of the silent film actresses in the teens soon learned to drive and reaching far greater numbers of people than books and stage plays, the moving picture undoubtedly played a decisive role in legitimizing woman's place at the wheel.The romance between the American film actress and the automobile began in 1908 at the Vitagraph studio in Brooklyn with the production of a one-reel film entitled An Auto Heroine. In those early days of the narrative film, the players' names were not listed so the identity of the daring actress who first took the wheel of a motorcar for the exciting race in An Auto Heroine was not revealed to the public. But the film, which has been preserved in the archives, was hailed as one of the more notable productions of the day by the reviewer for The New York Dramatic Mirror:

his highly dramatic scenes from initially quiet domestic imagery. Although as Pickford biographer Booton Herndon notes, 1912 was still "a time when few women even considered driving cars," (12) Mary takes the wheel of her large touring car as though it were already the most common of occurences. She plays a young motorist who picks up her boyfriend (Edwin August) in her car for a day's outing. But when he refuses to become involved in a quarrel with a tramp who insults him, Mary accuses him of cowardice and drives off alone. As the narrative unfolds, she will soon learn the meaning of true courage through both her own experiences and those of her rescuing boyfriend. For an escaped convict (Alfred Paget) highjacks her car and forces her to drive him through the countryside at top speed. From a distance, Mary's boyfriend sees her being kidnapped and commandeers a locomotive to join in a rescue attempt, a pursuit that also involves the driver of a racing car who follows the car being driven by Mary. Eventually, the convict forces Mary to go with him to a barn where she is finally saved from her nemesis by the timely arrival of her beau.

his highly dramatic scenes from initially quiet domestic imagery. Although as Pickford biographer Booton Herndon notes, 1912 was still "a time when few women even considered driving cars," (12) Mary takes the wheel of her large touring car as though it were already the most common of occurences. She plays a young motorist who picks up her boyfriend (Edwin August) in her car for a day's outing. But when he refuses to become involved in a quarrel with a tramp who insults him, Mary accuses him of cowardice and drives off alone. As the narrative unfolds, she will soon learn the meaning of true courage through both her own experiences and those of her rescuing boyfriend. For an escaped convict (Alfred Paget) highjacks her car and forces her to drive him through the countryside at top speed. From a distance, Mary's boyfriend sees her being kidnapped and commandeers a locomotive to join in a rescue attempt, a pursuit that also involves the driver of a racing car who follows the car being driven by Mary. Eventually, the convict forces Mary to go with him to a barn where she is finally saved from her nemesis by the timely arrival of her beau.In order to film "the most thrilling pursuit ever witnessed," (13) Griffith developed further his innovative cinematic techniques, making effective use of tracking shots to record the race between the locomotive and the touring car running parallel to the railroad tracks. (As has often been noted, A Beast at Bay anticipates a similar scene in the modern story of Intolerance, this time with a male driver at the wheel.) For closer shots of Mary and her passenger, Griffith and Billy Bitzer shot from a camera car at a safe distance ahead of her as the actress valiantly accelerated her vehicle.

Griffith's amazing technical virtuosity, at its early height in A Beast at Bay, had its match in Mary's extraordinary daring in driving the car at a fast speed. Griffith once said of her, "She will do anything for the camera. I could tell her to get up on a burning building and jump--and she would." (14) Dedicated to the new art of cinema and caught up in the spirit of women's emancipation which would soon make her the most important female in the industry, Mary had the boldness of a young pioneer, always willing to undertake new experiences. There were, of course, careful preparations for the making of A Beast at Bay. Biograph rented the touring car used in the film and its owner gave Mary the proper instructions in driving it. Nevertheless, Mary's mother, Charlotte, was terrified for her daughter's safety during filming. As Mary recalled a year later in an interview in The New York Dramatic Mirror:

Once she emerged as the queen of Hollywood, Mary, at the center of the world's attention, received publicity for every aspect of her life including the many cars she owned over the years. Although she often rode in her own chauffeured limousines, de rigueur for a star of her stature, Mary also had smaller cars that she drove herself. Particularly famous was a 1915 cream-colored Maxwell cabriolet which she acquired during a visit to New York. The car which Mary dubbed "Fifi" was shipped out to California and the actress was soon a familiar sight zipping around the nascent film capital's primitive roads. The Sunday motoring sections of the large newspapers ran numerous articles with photos of Mary and her Maxwell and it was also a topic in the fan and trade press. W. E. Wing noted in his column in The New York Dramatic Mirror:

I see no reason why a woman shouldn't drive her own car. I drive mine, and I drive it through the crowded streets of New York. You know the men say that women shouldn't drive cars because they can't keep their heads in time of accident. I don't believe that. If a woman has poise and is not nervous she is ready for any emergency."(19)

The new comedy offered Mabel a chance to exhibit her ability behind the wheel of a car as well as giving her another opportunity to demonstrate her new-found skill as a director. Mabel had learned to drive in the spring of 1913 while the Keystone Company was working in Mexico. (20) Her driving was apparently first put to cinematic use in The Speed Queen, one of the comedies that Sennett directed on location in Tijuana. Mabel's love of racing cars was often mentioned in the press in the teens. For example, during the filming of Tillie's Punctured Romance, Mabel had a running if largely mock rivalry with co-star Marie Dressler, a "feud" which they attempted to resolve by means of an auto race as reported in Movie Pictorial:

The day arrived. Miss Normand was there with her high power Bear Cat Stutz, while Miss Dressler drove a Fiat. Many fans were there but the weather made a postponement necessary."(21)

Reaching the Jersey side of the river our adventures began. Every one who motors knows that Fort Lee is one of the most dangerous spots in the East.

Mabel started up this young mountain at full speed, but the noble car got tired before we reached the top. Slowly, but surely, it was stopping. I looked around nervously, and my heart rose when I spied the water far, far below.

"Maybe I'd better walk?" I suggested non-chalantly. "The car might go easier if I get off."

Mabel just looked at me and laughed. "Oh, this is nothing," she said lightly. "Only yesterday, my machine backed all the way down, and if it wasn't for the ferryhouse, I would have been doing some water stuff without a camera in sight."

"Cheerful!" I remarked, and stealthily started for the ground, but returned to my seat meekly when I heard Mabel laugh and murmur.

"'Fraid cat!" (23)